Wilts & Berks Canal

The Wilts & Berks Canal

Jack Dalby

Jack Dalby

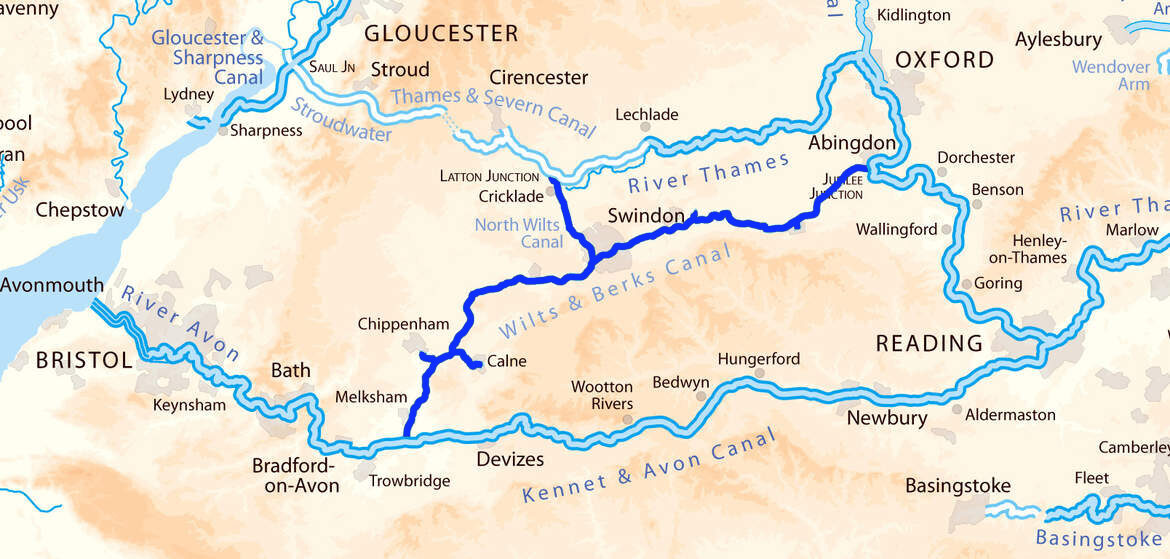

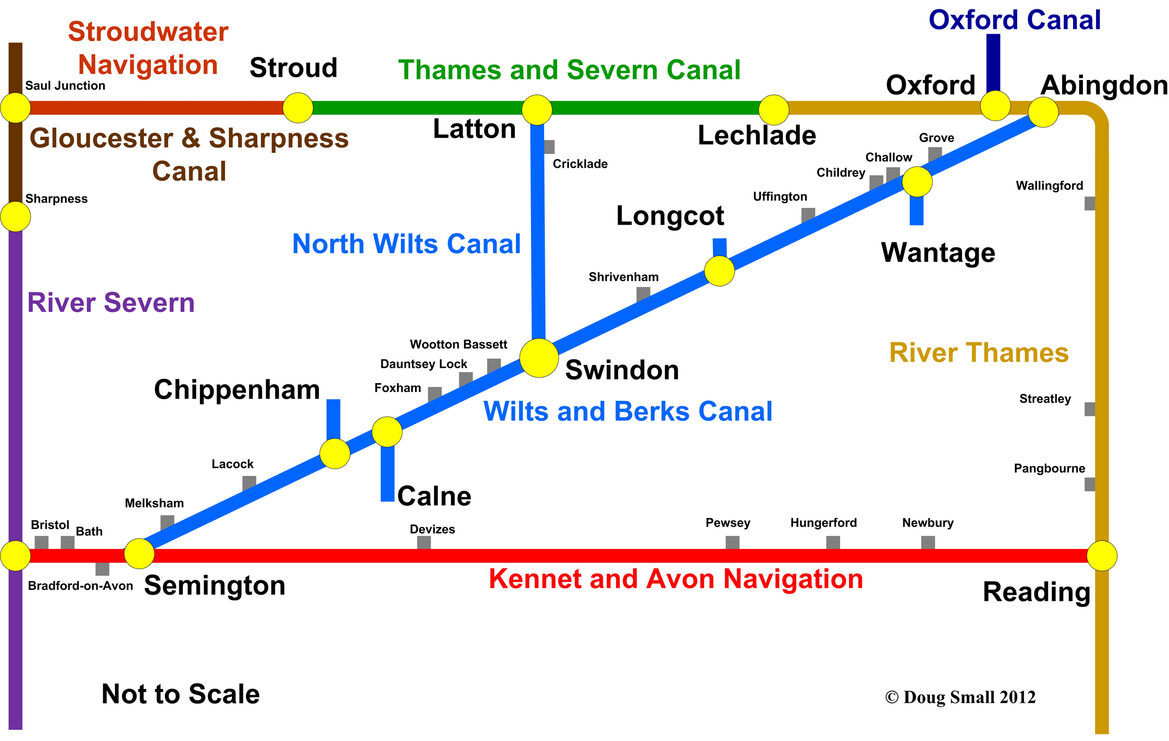

The course of the narrow Wilts and Berks Canal lay midway between its broader counterparts, the Thames & Severn to the north and the Kennet & Avon to the south. Schemes to improve the Thames & Severn’s prospects by bypassing part of the upper Thames, and an earlier, more northerly proposed line of the Kennet & Avon Canal, influenced the decision to build a canal linking the Kennet and Avon Canal at Semington and the Thames at Abingdon and possibly the appointment of Robert Whitworth and his son William, both involved in these abortive schemes, as the canal's engineers.

Discussion with the Kennet & Avon Canal in the design stages of both it and the Wilts and Berks Canal led to a choice of junction point advantageous to both - a most unusual circumstance! However, as it later turned out, the inclusion of 9 miles of the Kennet and Avon Canal as the link between the Wilts and Berks Canal and the chief source of its revenue, the Somersetshire Coal Canal, gave the larger company a convenient stranglehold in competing both for the coal trade of the districts between them and through traffic between Bristol and London. Apart from the tremendous disadvantage of the stretch of Thames between Abingdon and Reading, the Wilts and Berks Canal had the advantage of a more favourable route with 42 locks as opposed to 106 and a more sensible summit 9 miles long.

Work commenced at the Semington end late in 1795. The estimate for the 52 mile main line and the branches was £111,900. The effects of the Napoleonic wars and the fact that the link to the Somerset Coal Canal, so vital for the carrying of coal for brick burning and stone for bridges, lock parapets etc., was not completed until 1799, delayed the completion to September 1810 and boosted the cost to £262,000. The canal then settled down to its main purpose in life, the distribution of coal and stone to the Upper Avon valley and the Vale of the White Horse and even managed to compete at Abingdon with Midlands coal from the Oxford Canal (10,000 tons in 1818).

Scarcely had the main line been completed when proprietors launched schemes for ambitious extensions (1) to link their canal at Abingdon with the proposed Grand Junction Aylesbury arm; (2) a direct route from Foxham to Bristol bypassing the Kennet & Avon: and (3) a junction between their canal near Swindon and the Thames & Severn near Cricklade. (1) and (2) would have provided an all canal line from Bristol to London 154 miles long, 17 miles shorter than the combination of the Kennet & Avon and Thames Scheme (1) was opposed by the Grand Junction who neither wanted at that time to build the Aylesbury branch nor the competition of coal and iron from the west. Scheme (2) is would have been enormously costly and injurious to the Thames & Severn so it is not surprising that only (3) was acceptable! This, later, to become the North Wilts Canal, would. in theory at least, provide the Wilts and Berks Canal with an alternative supply of coal from the Forest of Dean via the Thames & Severn, the Somerset pits at that time not being able to satisfy both the Kennet & Avon and Wilts and Berks Canal it would also allow the Thames & Severn to bypass the upper reaches of the Thames.

The North Wilts, 9 miles long with 12 locks, was built 1813-19 for less than the estimated £60,000. It was soon in financial difficulty and was taken over by the Wilts and Berks Canal which had provided the majority of shareholders and all water. Forest of Dean coal was never popular on the Wilts and Berks line and before long more Somerset coal was being carried up the North Wilts than Forest coal came down. Between 1829 and 1839 the combination of the Gloucester & Berkeley, Stroudwater, Thames & Severn, North Wilts, Wilts and Berks and Thames carried a fast fly boat service between Gloucester and London, 5 days to the Capital and 6 days back.

The building of the Great Western Railway line made extensive use of the Wilts and Berks Canal, producing in 1840 the highest annual dividend of £9,000, but the railway then began to decimate canal traffic. In 1852, faced with inevitable ruin, the Company, following the example of the Kennet & Avon, offered their canal to the railway whose contemptuous offer of £20,000 was unwisely as it turned out, refused. From 1877 on, with traffic falling steadily year by year, a series of owners, lessees and Wilts County Council endeavoured to make the canal pay, but to no avail. Finally in 1914, Swindon Corporation, fed up with 3½ miles of derelict canal in its midst, obtained a Private Act to abandon the canal.

The building of the Wilts and Berks Canal was on a minor scale, no great aqueducts, no pumping stations or stupendous flights of locks as at Devizes on the Kennet & Avon Canal. The major engineering work was the two arched brick Stanley aqueduct over the river Marden near the junction with the Calne branch, the partial collapse of which in 1901 put paid to through traffic. The locks, 42 on the main line, 3 on the Calne branch and 12 on the North Wilts, could accommodate boats 72ft long 7ft wide, and carrying 25-30 tons. There are no records of other than horse or donkey drawn trading boats.